The first Christian woman to be sentenced to death under Pakistan’s blasphemy laws had her appeal rejected by the High Court in Lahore on Thursday.

Aasiya Noreen, commonly known as Asia Bibi, received the death penalty in 2010 after she allegedly made derogatory comments about the Prophet Mohammed during an argument with a Muslim woman.

While the two women were working together, the Muslim woman had refused water from Noreen on the grounds that it was unclean because it had been handled by a Christian.

The Muslim woman, together with her sister, were the only two witnesses in the case, but the defence failed to convince the appeals judges that their evidence lacked credibility.

Noreen, first arrested in the summer of 2009, has already spent five years in prison. Her defence team has one more opportunity to appeal her case by taking it to Pakistan’s Supreme Court.

Noreen was accused of blasphemy against the Prophet of Islam and the Quran in June 2009, when she was working in the fields as a laborer in Sheikhupura. A religious argument broke out between her and her co-workers after she brought water for one of them. One of her co-workers objected that the mere touch of a Christian had made the water haram, or religiously forbidden for Muslims. Noreen was told to convert to Islam in order to become purified of her ritual impurity. Her rejoinder was perceived as an insult of Islam and hence she was accused of committing blasphemy.

Muhammad Amin Bukhari, the Superintendent of Police who investigated Noreen’s case, testified in the trial court that the religious argument broke out over the drinking water, and not about the Prophet or the Quran. The trial court judge nonetheless convicted her and gave her the death penalty.

The case attracted international attention, and Noreen has had some high-profile supporters.

Pope Benedict XVI appealed to the Pakistani government for clemency. The then-Governor of the Punjab, Salmaan Taseer, went to meet Noreen in prison and prepared a petition for mercy, which he had intended to submit to the President of Pakistan.

Before Taseer could convey the petition to the president, his own police guard killed him Jan. 4, 2011 on account of his support Noreen and his characterization of the blasphemy laws as “black laws.” Two months later, the only Christian member of the cabinet, Shahbaz Bhatti, was killed. Bhatti had supported Noreen and sought to reform Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, which often are used to settle personal scores and pressure religious minorities.

The Lahore High Court began hearing the appeal in March this year, but the case kept circulating among several judges who postponed its hearing. Legal sources told World Watch Monitor that judges were unwilling to decide the case because of fear of reprisal from extremist elements.

Most of Thursday’s four-hour hearing was given over to arguments made by Noreen’s counsel, Naeem Shakir. The judges, Muhammad Anwar-ul-Haq and Shahbaz Ali Rizvi, postponed all other cases scheduled for the day. The complainant in the case, Muslim cleric Muhammad Saalam, was presented along with a few other men in the court. Saalam was represented by a group of lawyers headed by Ghulam Mustafa Chaudhry, a Supreme Court lawyer and president of the Khatme Nabuwat (Finality of Prophethood) Lawyers’ Forum.

Shakir argued that Noreen’s trial-court conviction had been based on hearsay, as Salaam himself did not witness the exchange between Noreen and her co-workers. He said it was at a local village council, or panchayat, where Noreen was forced to confess the alleged instance of blasphemy. The judges categorically stated that Pakistani law would not take into account any such confession made to a random group, and they set aside evidence of all the witnesses related to the village council.

The court, however, said that there were two sisters — Mafia Bibi and Asma Bibi — who had appeared in the trial court and testified they had witnessed the incident of alleged blasphemy. Shakir told the court that on the day it happened, Noreen had brought some water for other fieldworkers, and that the sisters refused to take it, saying they could not take water from the hands of a Christian woman.

Shakir said a quarrel arose between Noreen and the two women, which later was made to appear as a religious conflict. He said the nature of the quarrel had its source in the Hindu caste system (in which most Pakistani Christians are considered “untouchable”) than a conflict between the Christian and Islamic faiths.

Shakir said the evidence from the two sisters should have been corroborated by some independent evidence in the trial court, as these two sisters would have been prejudiced towards her. The appeals judges, however, observed that sisters’ testimony should have been challenged at the trial court, rather than taken up at the appellate court.

Attorney S. K. Chaudhry, who represented Noreen at her trial, told the appeals judges Thursday that as a Muslim he could not repeat the blasphemous words, so he did not cross-examine the two sisters because it involved discussing those blasphemous statements. One of the appeals judges responded that “in the process of administration of justice we need to be ‘secular.'”

Shakir was more successful when he argued the trial court had a religious bias against Noreen. Referring to the argument that took place between Noreen and two sisters, the trial court had noted the following:

“So, the question arises, what type or nature of hot words would be there in between Christian and Muslim ladies when the quarrel started from the refusal of drinking water by the Muslim ladies from the hands of a Christian lady. So, the phenomenon was ultimately switched into a religious matter and ‘hot words’ could not have been anything other than the blasphemy.”

Judge Anwar-ul-Haq brushed aside the trial judge’s observation, saying no judge in the world could infer whether “hot words” could be construed as blasphemy, or not.

Shakir also informed the court that the original complaint, known as a first information report (FIR), had been lodged by the cleric Salaam five days after the quarrel. He argued that, during the trial, the only reason given for the delay was “deliberation and consultation,” and said Salaam had acknowledged this in the trial court.

He said other appeals courts have ruled that if a delay in lodging an FIR is due to consultation and deliberation, the complaint should be dismissed. On Thursday, the appeals judges overruled Shakir’s argument, saying Noreen’s trial counsel hadn’t challenged this delay in the trial court, and therefore could not be taken up on appeal.

Shakir attempted to argue that the trial court did not have jurisdiction over Noreen’s case, citing a 1991 decision by Pakistan’s Federal Shariat Court that blasphemy cases, covered by Section 295-C of Pakistan Penal Code, came under Islamic shariah law. Referring to the landmark judgement he quoted the following words from the judgement:

“The contention raised is that any disrespect or use of derogatory remarks etc. in respect of the Holy Prophet comes within the purview of hadd (losely translated as ‘Islamic law’) and the punishment of death provided in the Holy Quran and Sunnah cannot be altered.”

He said witnesses in Noreen’s case should have had been tried under the special Islamic law of evidence, known as Tazkiya-tul-Shahood and the witnesses must meet the Islamic criterion of piety and religious observance.

If that were true, responded appeals judge Anwal-ul-Haq, the entire trial of Noreen should be declared unlawful. The judges then studied the Shariat Court’s ruling, but did not declare any finding.

Following the hours of argument, and without further deliberation, the judges announced “the appeal is hereby rejected,” which prompted jubilation among the lawyers representing the prosecution and Salaam, the original complainant.

After the hearing, Shakir told World Watch Monitor the court should have given weight to the serious flaws in the judgment and what he called the “biased mindset” of the trial court. He said with the passing of time it had become difficult for higher court judges to dispense justice, which, he said, “is increasingly in the hands of the extremists.”

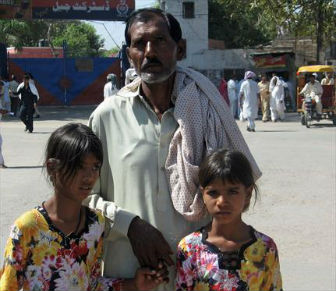

Though Noreen has been held in prison for the past five years, safety has been a serious issue for her. Her husband, Ashiq Masih, and their three children live in hiding in another city. In December 2010, a prominent Islamic cleric in Pakistan offered half a million Pakistani rupees (roughly US $5,000) for anyone who could kill Noreen. Since then, security around her has been increased in prison.

Masih told World Watch Monitor he’s hopeful the Supreme Court will provide justice to Noreen and that she will be released soon.

Pakistan’s judges have occasionally faced the wrath of countrymen upset with their decisions concerning blasphemy. Judge Pervez Ali Shah, who gave the death penalty to the guard who killed Salmaan Taseer, fled Pakistan after issuing his decision. Justice Arif Bhatti, who had acquitted two Christians in a 1995 blasphemy case, was killed in his office in 1997.

In its most recent annual report, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, and advisory body to Congress, urged the government of Pakistan to “place a moratorium on the use of the blasphemy law until it is reformed or repealed” and to unconditionally pardon and release those accused under that law. The law is widely popular, however, putting pressure on the government, including the courts, to preserve it.