This came four days after the murder of a local journalist, who’d reported extensively on links between organised crime and politicians.

Chihuahua’s largest city, Juarez, on the border with the US state of Texas, used to be known as the murder capital of the world. From 2007-2014, thousands of people were killed every year in Juarez in violence related to organised crime. In 2011, the death toll across Mexico was greater even than in Syria and Juarez was at the centre of it.

A period of relative calm has followed – though dozens are still killed every month – but a local church leader fears another crescendo of violence is around the corner.

Most of the violence is drug-related and centres on Mexico’s 3,000km-long northern border, where cartels seek to take Class A drugs on the final leg of their journey from South America to the States.

Given that as many as 90% of Mexico’s population would identify as Christian, Petri says “it’s important not to look so much at their identity as Christians, but more at their behaviour that results from their Christian convictions. Whenever a Christian starts to engage in social work – for example setting up a drug rehabilitation clinic or organising youth work, that is a direct threat to the activities and interests of organised crime because it takes the youth away from them, so it is a direct threat to their market.”

Petri mentions one church leader who was killed for setting up a drug rehabilitation clinic and then refusing to close it despite threats. He also cites the example of another church leader who set up a football team for vulnerable boys, some of whom were working as informants for cartels. When one boy then told the cartels he no longer wished to be an informant, he was killed.

A more obvious example of why active Christians are easy targets comes from the perception that churches and their leaders have a lot of money, so congregations offer a ready source of cash – cartels can simply enter, lock the doors and ask the congregation to empty their pockets.

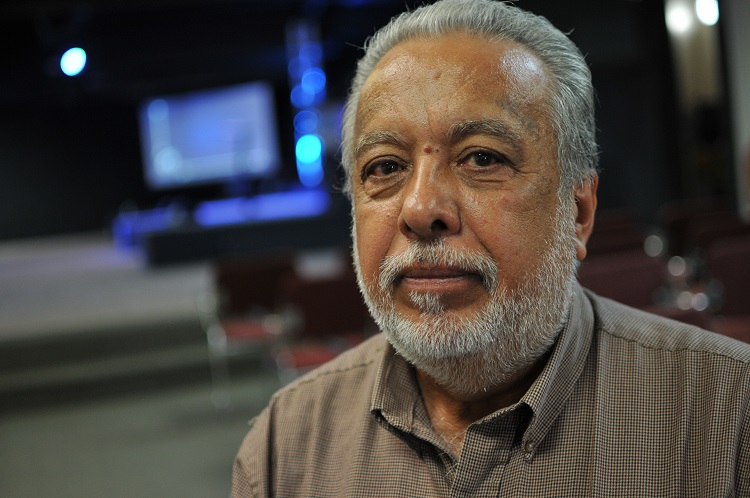

Chito Aguilar, 62, a former drug trafficker who now leads a church, told World Watch Monitor: “Compared to a convenience store, they say, ‘Well if in a church there are 40 or 50 people, or 100’ – because [the cartels] do this on Sunday, not during the week – they say, ‘So they will bring money, they’re going to give their offerings’. So they become an easy target, because [the cartels] will come here, as they do here in Ciudad Juarez: eight people walk into a church, one or two will remain at the doors and the others will start collecting watches, rings, wallets … everything. So they become an easy target of the attackers.”

There was a period, says Aguilar, when Christians were viewed as particularly susceptible to extortion because they would always pay. Church leaders, or members of their family, were kidnapped and a ransom demanded.

Adrian Lara, a musician at Aguilar’s church, said: “The city of Juarez has been known around the world because the violence has been really hard. Today, in 2017, it’s less prevalent. But in 2012, it was very terrible. Every businessman was called by people, who said: ‘If you don’t pay, we are going to kill your children, or burn your house. We are going to do many things to you if you don’t pay’.”

But some now refuse to pay. Aguilar even says he actively encourages his congregants to do the same. He says the tactic has worked, but that he fears the violence is on an upward curve again.

“Seven years ago, the situation was very difficult in Ciudad Juarez,” he says. “Lots of pastors were kidnapped, their children killed. It seems like for four years we had a period of calm, but in the last year the violence has started increasing again. Pastors are starting to be extorted, leaders threatened with kidnapping, and I believe that among the pastors there is fear because of what we lived and experienced seven or eight years ago.”

With such large sums of money involved, corruption is inevitable, and fear pervades. World Watch Monitor had arranged interviews with three pastors and a pastor’s daughter, each of whom had suffered at the hands of the cartels – whether through kidnapping, threats or extortion – but interviews were either cancelled or phone calls repeatedly ignored. It is little wonder that people are scared when violence so abounds.

But some did agree to talk. And the picture they painted was gruesome.

One pastor, Eduardo Garcia, described the moment he learnt that his son Abraham, who was 24, had been killed, during the height of the violence in October 2009.

“The telephone rang and I heard my wife yell. I was on the second floor, but I heard her cry ‘No!’ very loudly,” he said. “So I went downstairs quickly and asked, ‘What happened?’ And she just said, ‘They killed Abraham’.

“The pain we feel is really strong. We wouldn’t wish it on anyone… We had decided to try to rescue the city, but I never imagined we would become a part of the statistics.”

Eighteen months later, Garcia’s daughter, Griselda, was kidnapped and her father was forced to pay a ransom to secure her release.

Jorge Rodriguez, the Director of Religious Affairs for the city government, says the trials of the Garcia family shine a spotlight on crimes that in many cases go under the radar.

“These [criminal] groups are affecting the whole city and especially the Christian community because we are a people of peace,” he says. “In many cases, the abuses are not even reported, but we have specific cases of pastors being kidnapped and children of pastors being kidnapped, such as in the case of Pastor Eduardo Garcia and his family.”

Life in Ciudad Juarez is still fraught with danger. Fear pervades. And Christians are caught in the middle.