For the sixth time since the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the government of constitutionally “secular” Turkey has openly intervened in the selection of a new Armenian Patriarch to lead the nation’s largest Christian community.

Now estimated at less than 40,000, Turkey’s Armenian community – located primarily in Istanbul – are the remnant of some 2 million Armenians who had lived in central Anatolia and the eastern regions of what is now modern-day Turkey for two millennia. An estimated 1.5 million died during massacres and forced deportations into the Syrian Desert, begun in April 1915 under the Ottoman Empire. Although Turkey acknowledges there were “casualties on both sides” during this time in World War I, it denies the events constituted a “genocide”.

Armenia was the first country in the world to adopt Christianity as its state religion (in 301 AD). Today Istanbul’s historic Armenian Patriarchate oversees 42 churches and more than 50 community foundations in Turkey, supporting their minority schools, hospitals, cemeteries and various charitable projects to meet the religious, educational and humanitarian needs of the community. But in early February, the Clerical Council of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate was ordered by the Turkish state to abandon its efforts over the past 18 months to replace the incumbent Patriarch, who fell seriously ill ten years ago and is now in a coma.

Two years into his illness, Patriarch Mesrob II Mutafyan was diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Since he could no longer carry out his duties, the Armenian community debated two options: either electing a new Patriarch, or a temporary Co-Patriarch to fulfil Mutafyan’s responsibilities until his death.

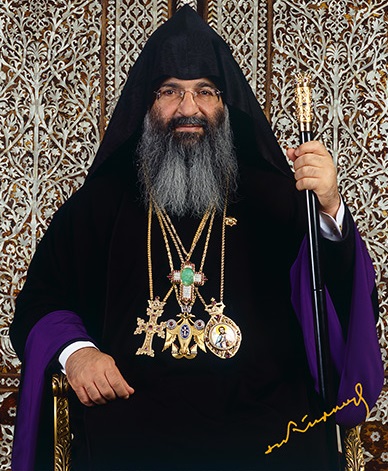

But in 2010, the Turkish government argued that neither election would follow Armenian Church traditions, under which the Patriarch had either died or resigned before his successor was elected. Instead, the state invented a new leadership role within the local church hierarchy: a Patriarchal Vicar General to handle the day-to-day affairs of the patriarchate. The Clerical Council then selected Archbishop Aram Ateşyan to fill this new post established by the government.

Ateşyan remained in this state-appointed role as the de-facto leader of Turkey’s Armenian community for the following years. But in October 2016, the Clerical Council officially retired Patriarch Mesrob, stating that his incurable condition had rendered him unable to perform his duties for the past seven years. At that point, the Armenian community’s expectations focused on launching the election process for a new Patriarch.

But Ateşyan stalled for months, declining to interact openly with government officials to begin election proceedings. Finally in February 2017 Bishop Sahak Maşalyan resigned in protest as head of the Clerical Council. “The election atmosphere – always on the agenda, but never resolved – provides the ground for church divisions and conflicts,” Maşalyan explained to religious-freedom watchdog Forum 18 last week.

Widespread community support soon prompted Maşalyan to withdraw his resignation. The Clerical Council then declared the patriarchal seat vacant, calling for the election of a locum tenens (temporary leader) to begin and oversee the election process.

In addition to Ateşyan and Maşalyan, two other Armenian clergymen serving as spiritual leaders of Armenian communities abroad were eligible as Turkish-born citizens and willing to oversee the election process: Archbishop Sebuh Çulciyan in Armenia and Archbishop Karekin Bekçiyan in Germany.

In an election at 3pm on 15 March, 2017, Bekçiyan was elected, with a two-thirds majority over the other candidates, to serve as the locum tenens. Minutes later, Ateşyan produced a previously undisclosed letter from the Istanbul Governorate that had been faxed to the patriarchate earlier that day, declaring it was “legally impossible” for the church to proceed with patriarchal elections. Stating that the Patriarchal Vicar General was still in charge of patriarchate affairs, the letter released to the press warned that starting election activities could “cause splits in the Armenian community”.

Pointedly, Istanbul’s weekly Armenian Agos newspaper reported that the letter from the Governor’s office had been faxed to the patriarchate at 1.47pm, more than an hour before the election was held. By implication, apparently only Ateşyan knew before the vote took place that the government was forbidding the election.

Bekçiyan was invited to come from Germany in early April to take up his temporary canonical position in the Istanbul patriarchate. But Ateşyan refused to resign from his own state-appointed post. As a result, in late June the Clerical Council voted 22 to two to remove Ateşyan from his Vicar-General role.

Seven-month stalemate

But for the seven months since, the Turkish state has declined any interaction with Bekçiyan, leaving unanswered all his letters and requested appointments as the Armenian Church’s chosen spiritual leader. The only public government contact with the community was channelled through prominent lay businessman Bedros Şirinoğlu, who heads one of the largest Armenian community foundations and met last spring with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Frustrated by the ongoing official silence, the patriarchate’s Election Steering Committee finally filed a complaint against the Interior Ministry earlier this month for its failure to respond to the Church’s application to begin the election process.

On 6 February, the Istanbul Governorate broke its silence in a written response to the Patriarchate, declaring that “conditions for the election of a new Patriarch have not materialised” – i.e. Patriarch Mesrob is still alive, health reasons do not leave his position vacant, and Ateşyan is still the Patriarchal Vicar General, the letter stated.

The next day, laymen heading the Armenian community’s foundations were summoned along with the patriarchate’s lawyer to meet with Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu at Istanbul’s Çırağan Palace. None of the church’s spiritual leadership were invited, but Soylu was flanked by Istanbul Governor Vasip Şahin as well as the Istanbul Chief of Police, the Istanbul gendarmerie commander-general and several other senior officials.

Attorney Sebouh Aslangil told the Interior Minister that the Armenian Clerical Council had taken all its actions over past months in accordance with church rules, including removing Ateşyan from his post as Patriarchal Vicar General.

But Soylu insisted that Turkey was “acting under the law”, saying it was the state’s duty to recognise the role of the patriarchal vicar.

“The government has openly intervened in the traditions of the church and told them that they cannot elect their own Patriarch.”

Agos

Quoted by CNNTURK on 8 February, Soylu specified that a ruling by the Turkish Council of Ministers on 29 June, 2010, had decreed that “until Mutafyan died, Aram Ateşyan would remain as the Patriarchal Vicar-General”.

After several representatives of the community explained why it was important for the patriarchal elections to take place immediately, Soylu said he would convey their concerns to President Erdoğan and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim. “We must meet again in about a month,” he concluded after the three-hour meeting.

Later that day, an Agos editorial concluded: “The [ruling] AK [Justice and Development] Party government has openly intervened in the traditions of the church and told them that they cannot elect their own Patriarch.”

On the heels of Soylu’s meeting, the Clerical Council bowed to the government interference the next day, formally reinstating Archbishop Aram Ateşyan on 9 February as the “acting” Patriarch. Four days later, Bekçiyan returned to Germany, describing the Turkish government’s interference as a “long and planned campaign” to sabotage Turkey’s 85th patriarchal elections.

Established legal vacuum

“It’s an ‘established practice’ that the [Turkish] state interferes in how some religious communities elect their leaders, particularly the Armenian, Greek Orthodox and Jewish communities,” Forum 18 said last week in a detailed review of the recent patriarchal elections saga.

Essentially, it said, the absence of a legal framework for Turkey’s Armenians and other non-Muslim minorities continues to violate the country’s international religious-freedom obligations, as spelled out in the Lausanne Treaty and its own constitution.

“The real problem lies in the absence of any law on the institutions of religious minorities, and the Turkish government’s refusal to recognise those institutions as legal personalities,” Turkish human-rights lawyer Orhan Kemal Cengiz told Al-Monitor last year.

Without a legal framework to protect their full religious rights, Turkey’s Armenian citizens remain dependent upon the political “good will” of the government in power to even choose their own spiritual leaders.