The motive behind the murder of a Fulani Christian politician in Mali last month remains unknown, but locals suspect an Islamist agenda.

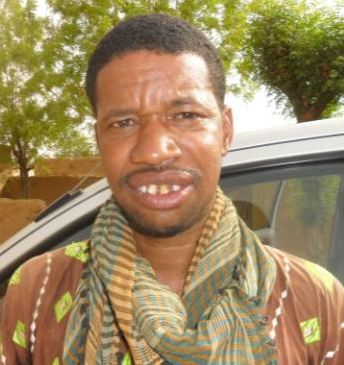

Moussa Issah Bary, the 47-year-old deputy mayor of Kerana (near the Burkina Faso border), was shot dead by six unidentified men on motorbikes on 16 November. He is survived by a wife and eight children.

Bary’s murder came just days before municipal elections. He was a rare example of a Christian member of the Fulani tribe, some of whose militant extremists have become infamous in Nigeria for committing atrocities which have seen them named as one of the top five deadliest militias in the world.

“This tragedy has sent sadness, fears and concerns among the Fulani Christians in several countries, most of whom knew Moussa or just heard of this brutal death,” a local source told World Watch Monitor. “Until now, there has been no official claim from the actors of this disaster.

“We do not know whether it is because of his faith that he was brutally attacked or because of his political position.”

Mali has suffered from a wave of Islamic extremism in recent years, since militants and foreign fighters made common cause with Tuareg rebels to take over a large portion of the country in 2012. For most of that year, until the French military were forced to intervene, armed Islamist groups ruled the region, banning the practice of other religions and desecrating and looting churches and other places of worship.

Since then, Mali has been blighted by regular Islamist attacks, including the recent |bombing of two airports{/link} in the north of the country and, earlier in the year, the kidnapping of a Swiss missionary, whose whereabouts is still unknown.

In June, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb released a video, purporting to show that Beatrice Stockly, who was kidnapped for the second time in January, was still alive. The three-minute video showed a veiled Stockly speaking in French, saying that she has been detained for 130 days but was still in good health and had been treated well.

During the 2012 occupation, thousands, including many Christians, fled and found refuge in the south, or in neighbouring countries such as Niger and Burkina Faso. Others fled to Bamako, the capital, and other safer towns in the south.

Unlike other Christians, Stockly remained in Timbuktu. At her mother and brother’s urging, she returned to Switzerland after her 2012 kidnapping, but soon returned, saying, “It’s Timbuktu or nothing”.

The Malian government and the predominantly Tuareg rebel groups signed a peace agreement in June 2015, with limited impact. Jihadist groups have regained ground and intensified attacks, targeting Mali security forces and UN peacekeepers. Their scope has spread to southern regions previously spared by their incursions.

In December last year, three men were killed when an unidentified gunman opened fire outside Radio Tahanint (Radio Mercy in the local dialect), which is closely linked with a Baptist Church in Timbuktu. A month earlier, terrorists had killed 22 people at the Radisson Blu Hotel in Bamako.

Islamic extremism in Mali is part of a wider regional problem. Across Africa’s vast Sahel region, which spans the width of the continent, jihadist groups such as Ansar Dine, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Boko Haram and Islamic State are all active.

A September report from Open Doors, a charity providing support to the global Church under pressure, said that the rise of Islamist militancy in the region is undermining freedom of religion.

According to the report, puritanical and militant versions of Islam (particularly Salafism/Wahhabism) are increasingly taking root – in a manner that reflects recent developments in the rest of the world – as a result of Islamist missionaries and NGOs from the Middle East, funded by (until recently) oil-rich Gulf States like Saudi Arabia and Qatar.