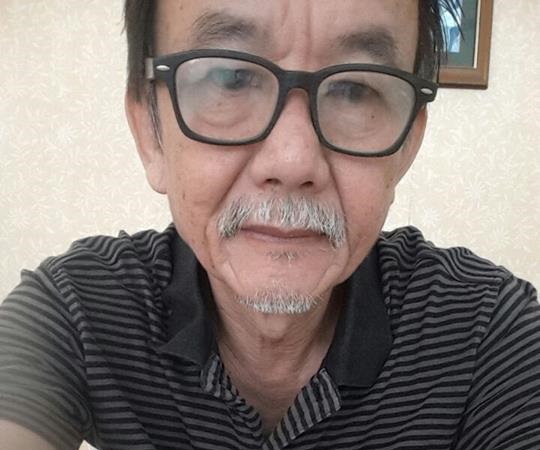

The fragile hopes of a Malaysian family in search of answers to the abduction of church leader Raymond Koh were dashed by a surprise development on Wednesday (17 January).

Almost a year after Koh went missing, after little or no progress in police investigations, Malaysia’s newest Inspector General of Police informed a human rights inquiry trying to trace what had happened to the Christian pastor that a man has been charged this week with his kidnap.

This sudden interjection meant that the country’s Human Rights Commission, SUHAKAM, had to halt its scrutiny because the law specifies that its power to hold an inquiry ceases when court proceedings against a suspect are activated.

Koh was kidnapped on 13 February last year by at least 15 masked men driving black 4×4 vehicles. They ambushed his car in a military-precision operation that was caught on CCTV.

Koh was bundled out of his car and carried away. His vehicle was also taken and has not been found.

Video footage of the abduction in broad daylight was shared widely and shocked the nation.

Hopes ‘crushed’

The police action that led to the termination of the inquiry was received with stunned silence at SUHAKAM’s offices in central Kuala Lumpur, where the hearings are being held.

Koh’s family, lawyers, journalists and civil society organisations monitoring the inquiry had no inkling of what was about to transpire, even though a suspect was charged with the abduction two days ago.

Moreover, police witnesses who were scheduled to testify on Tuesday (16 January) boycotted the inquiry.

Koh’s wife, Susanna Liew, 61, said the family was “crushed” by the abrupt end to the inquiry, as they had come to find answers to the many questions they have over Koh’s disappearance.

“It is very shocking for us as a family, as we had no idea this was going to happen,” she said. “We hope that there will be justice. We still have hope in the system but I’m afraid today this hope has been crushed.”

The civil society coalition, Citizens Against Enforced Disappearances (CAGED), said the latest development was “shocking” and “illogical”.

CAGED said it beggared belief that a person was charged in a case that had gripped the nation, and yet the police had not said a word to the media or anyone else except SUHAKAM.

It accused the law enforcement agencies of deftly trying to shut down the inquiry because the evidence heard in 12 days of sittings had embarrassed the police.

The jaw-dropping development arose when the police chief, Mohamad Fuzi Harun, sent a letter to SUHAKAM, stating that a part-time Uber driver, Lam Chang Nam, had been charged with Koh’s kidnapping, and a case is now pending.

Who is Lam Chang Nam?

Lam, 31, was charged in March last year with attempting to extort $30,000 Malaysian dollars (US$7,600) from Koh’s son for the release of his 63-year-old father. He denied the charge.

At that time the police cleared him of any involvement in the actual kidnap, and, 10 months later, he has again pleaded not guilty to the latest charge of kidnap.

The inquiry had provided a glimmer of hope to Koh’s family, Malaysia’s minority Christian population, and the public, that if state actors had been involved in the kidnap they would be held responsible for their actions.

In a statement police chief Mohamad Fuzi said: “Investigations are still ongoing and we have found a new lead that associates Lam with Koh’s abduction.”

He added that a hunt is on for seven others still at large, who are linked to the case.

Over the year public focus on the kidnap, and candlelight vigils for Koh’s safe return – which attracted large crowds in Kuala Lumpur and the administrative capital, Putrajaya, and in the states of Sabah and Sarawak – rankled with the police.

In March last year Mohamad Fuzi’s predecessor, Inspector-General of Police Khalid Abu Bakar, ordered the media to “please shut up” and stop reporting and talking about Koh’s kidnap. He also wanted an end to the vigils. The threats had their effect and the wakes have been less frequent, with fewer attending.

Other missing Malaysians

Koh’s disappearance in an urban environment in, until recently, moderate-Muslim Malaysia is one of a number of “missing” cases SUHAKAM is investigating.

The national human rights commission is also investigating the disappearances of social activist Amri Che Mat, Pastor Joshua Hilmy and his wife Ruth Sitepu.

Amri, the founder of non-profit organisation Perlis Hope, went missing on 24 November 2016. His vehicle was found abandoned.

There has been media speculation that he was promoting the Shia ideology, a branch of Islam that the majority-Sunni Malaysian Muslims reject. Amri’s wife has denied the alleged link to Shi’ism.

Joshua Hilmy, a Malay who converted to Christianity, and his wife Ruth, a Christian from Kalimantan in Borneo, were reported missing on 6 March 2017.

Non-Muslim minority groups remain concerned they could have been abducted by Muslim vigilantes, given the rise of an intolerant strain of Islam in Malaysia that seeks to impose Sharia (Islamic law), mandating amputations.

Their cases, as well as Koh’s, are being closely watched because police have been unable to provide answers after months of investigations.

‘They know what happened’

Close friends of the Koh family who attended the inquiry, which last sat in November before reconvening this month, said police were refusing to disclose any information.

“They know what has happened,” one source, who wanted to remain anonymous because “people are being followed and live in fear of also being abducted”, told World Watch Monitor. “The government can’t play with people’s lives.”

Concerned Malaysians are also asking why the police were less than forthcoming in helping SUHAKAM to uncover the truth, and appeared to want to stop the inquiry.

They said the reputation of the Royal Malaysian Police, respected for its competent track record in solving crimes, is at stake.

The chairman of SUHAKAM, Razali Ismail, acknowledged yesterday that the Koh case was a matter of huge public interest.

“The family has come to talk to us for all these months,” he said. “We really must understand their concerns and, more importantly, the public’s concerns and the various implications. In no way will SUHAKAM pull back from this investigation.”

Razali also said that the commission would play a very “constructive” role in the trial, and that it would do whatever was required, within legal boundaries.

Police criticised

Koh’s family were incensed last year when they heard police had been investigating whether the pastor had been proselytising Muslims, instead of focusing on pursuing his captors. In 2011 Koh had been accused of proselytising Muslims, and had also received bullets in the mail.

While freedom of religion is enshrined in the Malaysian constitution, the government forbids conversion of Muslims.

Koh’s wife Susanna had testified before the public inquiry that her husband had always been very careful to remind staff at his charitable organisation that they were not to proselytise, though she said the charity was “not linked to any religion” and was “not a Christian entity”.

Thomas Fann, from CAGED, claims there has been a lack of urgency in police investigations in all missing-persons cases.

His organisation has also catalogued the disappearances of five other Malaysians of Indian origin in 2011, 2013, 2015 and 2016, some of whom were taken by men in uniform.

CAGED claims that there was little or no public outcry then because they may have been involved in gang-related activities, and such disappearances were a modus operandi the authorities used to deal with “troublesome people”.

“We didn’t care then, but now religious minorities are being targeted,” Fann said.

CAGED wants the rule of law to apply to all citizens; for police to use all the resources available to them to resolve who is behind the abductions; for no-one to be denied a fair trial; and for families to be provided with regular updates of investigations.

Malaysian Christians meanwhile fear that if Lam is convicted of Koh’s kidnap, or even freed because of a lack of evidence, the human rights inquiry will be stalled for a long time and the hope of justice for his family will be more than likely snuffed out.